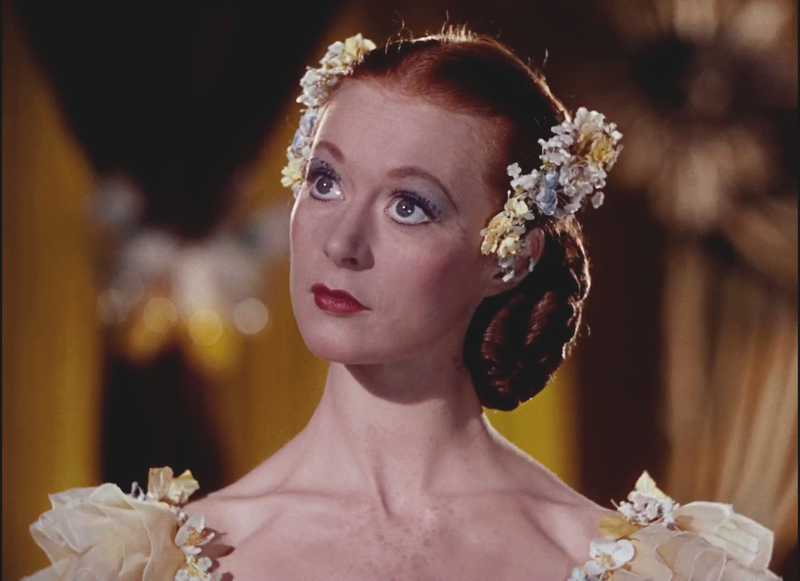

Moira Shearer, geboren am 17. Januar 1926 in Dunfermline, Schottland, tanzte seit 1942 am Sadler’s Wells Theatre, der führenden Bühne für Ballett in London, und stieg dort auf zur Primaballerina. Sie ist in drei Filmen von Michael Powell und Emeric Pressburger zu sehen, 1948 im Wunderwerk „The Red Shoes“, dem Ballett-Kultfilm schlechthin; 1951 in „The Tales of Hoffmann“; 1959 in „Peeping Tom“, jenem brillanten Film, der Michael Powells Karriere als Regisseur in Schutt und Asche legte.

1944 glänzt Moira Shearer als Odile in „Schwanensee“:

„In her black and gold dress, Moira Shearer had a burnished beauty that night that caught the breath as she made her dramatic entrance. Triumphant, evil, she took the stage with glittering assurance and slipped with ease into the exacting pas de deux and variations with a noble and romantic partner in David Paltenghi. With swift and dramatic touches she cast her spell over Prince and Court alike and then in a flash of baleful black and gold movement was gone, leaving an audience under an enchantment as irresistible as that woven in the tale.“ [1]

Zwei Jahre später begeistert sie als Aurora in „The Sleeping Beauty“,

„In the opinion of Arnold Haskell, one of the foremost ballet critics, she had a magnificently fluid style, great and unusual beauty and a fine intelligence. He wrote: ‚Shearer has an attack and self-possession altogether unusual in a young British dancer, gaining the sympathy and then the enthusiasm of the audience from the moment she stepped on the stage'“ [2],

1948 als Giselle (The Times: „… a performance outstanding for its poetry and lyricism“, 3)

und als Cinderella:

„Through it all Shearer moved with lyrical enchantment. In the first act she invested the part with a simple pathos and a wistful humour as, with her broom for a partner, she danced in imagination at the ball. Her arrival at the Palace was the crowning moment of the ballet. She was the fairy-tale princess of everyone’s dreams.“ [4]

Musical Opinion: „Moira Shearer made a most appealing Cinderella. The role suits her and her imagination and intelligent control of her technique, both of dancing and of mime, enabled her to suggest, unerringly, the many and swiftly changing emotions to which the little maiden is subject during the first really exciting moments of her life. (…) With Michael Somes, a noble and ardent Prince Charming, she is at her radiant best.“ [4]

Michael Powell in einem Interview über „The Red Shoes“:

„The salient feature of this film is simply Moira Shearer. Before this film could be started it was necessary to find a dancer on the brink of becoming a ballerina, about twenty years of age; beautiful; exquisit figure and legs; strength of character; who could dance all the classical parts; and finally a dancer who could act and not an actress who pretended to dance. If we had not found Moira Shearer we could not have made this film.“ [5]

„The press show of The Red Shoes followed ten days after her appearance as Giselle. Professional film previews are usually cold, unenthusiastic affairs but half way through the film, when the ballerina bows before the curtain at the end of the ballet, hardened critics burst into applause. An American reporter there said he had never heard this happen in all his experience of press shows. The same thing occurred at the premiere on July 18th.“ [6]

[Entwurf von Hein Heckroth für „The Red Shoes“]

Martin Scorsese, 2009 [independent.co.uk]:

„The first word that comes to mind about Moira Shearer in The Red Shoes is ‚radiant,‘ particularly in the way she was lit in the film and the angles used in her close-ups. The combination of actor/dancer seemed so natural for her. The nature of her physical build said so much about the character, even just a glance from her or a close-up.

The colour, the way the film was photographed by the great Jack Cardiff, stayed in my mind for years. The film would be shown every Christmas on American television in black and white, but it didn’t matter – we watched it. Even though it was in black and white on TV, we saw it in colour. We knew the colour. We still felt the passion – I used to call it brush-strokes – in the way Michael Powell used the camera in that film. Also, the ballet sequence itself was like an encyclopedia of the history of cinema. They used every possible means of expression, going back to the earliest of silent cinema.

It is a film that I continually and obsessively am drawn to.

The movie that plays in my heart.“

Allison Shoemaker, 2016, consequence.net:

If The Red Shoes was a bad movie, but with all the dancing intact, it would still be remarkable. Watch the film’s central ballet alone and you’re seeing one of the greatest sequences ever committed to celluloid. But even though the ballet scenes are easily the film’s most striking, dance is a bit of a red herring. The Red Shoes isn’t a dance movie … The Red Shoes is a movie about life.

As played by the luminous (an overused word, justly applied here) Moira Shearer, a ballerina making her film debut, Victoria begins the film with only one desire: to dance. Her drive steers her into the path of ballet luminary Boris Lermontov (the remarkable Anton Walbrook), who is completely uninterested until he sees that glint of possession in her eyes. „Why do you want to dance?“ he asks her. „Why do you want to live?“ she responds.

You learn everything you need to know about what comes next in that central, 20-minute ballet. It’s hallucinogenic, non-literal — no stage in the world has ever looked like that — and more about Victoria’s inner conflict than it is about Anderson’s tale. She’s consumed by her art but beginning, ever so slowly, to fall in love with the very person whose music underscores her thoughts. On one side, the man who would make her a truly great artist. On the other, the man who could make her happy. On her feet, the red shoes. How could anyone not be torn apart?

Whatever Powell and Pressburger sacrificed of themselves to get the film made, whatever deal with the devil or pound of flesh it required, it seems to have been worth it. The Red Shoes is a terrifying, visually stunning piece of filmmaking, and its distinctive aesthetic (thanks largely to the Oscar-winning work of German painter and theatre artist Hein Heckroth) keeps its surrealist landscapes from seeming even the least bit dated.

While beloved by cinephiles — Martin Scorsese cites the film as a favorite and personally spearheaded a seven-year restoration effort, the results of which can be seen on Criterion’s DVD release — The Red Shoes seems to have slipped from the larger cultural memory. It’s unlikely to come up in a round of pub trivia or shown in a double-feature with All About Eve (another great backstage film, which won the big award two years later). But watch it, and try not to wonder about who else is making such a choice, what artist is running away from a life of warmth and love in pursuit of a beast that never stops feeding. Watch and just try to forget it.

„The red shoes,“ Lermontov says, „are not tired. In fact, the red shoes are never tired.“

„The Tales of Hoffmann“ ist ein weiterer Lieblingsfilm von Martin Scorsese, und auch George A. Romero, der Regisseur von „Night of the Living Dead“, ist ihm verfallen: „I was just enthralled by it. Some of the imagery just sticks with you. It was the first music video, as far as I’m concerned.“ (Romero)

[1] Pigeon Crowle: Moira Shearer – Portrait of a Dancer, London 1949, 35

[2] Crowle, 47

[3] Crowle, 64

[4] Crowle, 69

[5] in: Crowle, 56

[6] Crowle, 65

2 replies on “Moira Shearer”

Psst. Ich weiß da noch einen Fan: Kate Bush „The Red Shoes“.

LikeGefällt 2 Personen

„I’d never trained in ballet, just modern dance. I went up on point for the first time while training for the film that went with this album. I am in awe of every ballerina. There’s nothing like the feeling, but it really hurts!“

Gelernt hat sie u.a. bei Lindsay Kemp, der ja auch mit David Bowie zusammengearbeitet hat, jedenfalls beweisen fast alle ihre Videos, daß sie selber eine exzellente Tänzerin ist!

LikeGefällt 2 Personen