Edward Burne-Jones

Portrait of Maria Zambaco

1870

Maria Zambaco, eigentlich Maria Cassavetti, geboren am 29. April 1843 in London, Tochter eines wohlhabenden griechischen Kaufmanns, Muse der Präraffaeliten, Modell für James Abbott McNeill Whistler und Dante Gabriel Rossetti, von ihrem Verehrer George du Maurier beschrieben als „rude and unapproachable but of great talent and a really wonderful beauty“. 1860 heiratet sie in London den Arzt Robert Zambaco, 1861 ziehen beide nach Paris. 1866 trennt sie sich von ihm und geht mit ihren beiden Kindern nach England zurück. Ihre Mutter Euphrosyne Cassavetti bittet Edward Burne-Jones, ein Porträtbild ihrer Tochter anzufertigen und Marias eigene Kunststudien zu fördern. Maria und Burne-Jones beginnen eine Liebesbeziehung. Im Januar 1869 findet Burne-Jones‘ Ehefrau Georgiana einen Brief von Maria in seiner Kleidung, die stürmische Affäre wird öffentlich und löst einen gesellschaftlichen Skandal aus. Maria fleht ihn an, gemeinsam mit ihr Selbstmord zu begehen durch eine Überdosis Laudanum, Burne-Jones trennt sich von ihr. Es entsteht eine Reihe von Bildern mit Marias Antlitz, das für den Maler ewige Obsession bleibt. Maria Zambaco beginnt in den 1880er Jahren mit der Bildhauerei und wird in Paris Schülerin bei Auguste Rodin. Das Porträt, das Burne-Jones 1870 malt, nach der Trennung, ist eine Liebeserklärung an Maria und Verewigung der Amour fou.

„Independently wealthy, unconventional, tempestuous and determined, she was a lover who refused to be quietly adored and Burne-Jones began to see that she wanted more than he was prepared to give.

When he told her that he would never leave his ever-faithful wife Georgiana, Maria was enraged and Burne-Jones took flight, leaving her ‚tearing up the quarters of his friends‘ to use Rossetti’s words. When he eventually returned, she threatened to kill herself and there was an embarrassing scene beside the Regent’s Canal where Burne-Jones was almost arrested for rolling in the gutter with Maria as he prevented her from leaping into the water. The storm had broken and the affair was over but they remained in contact and Maria’s face continued to dominate Burne-Jones‘ art.“ [Simon Toll, sothebys.com]

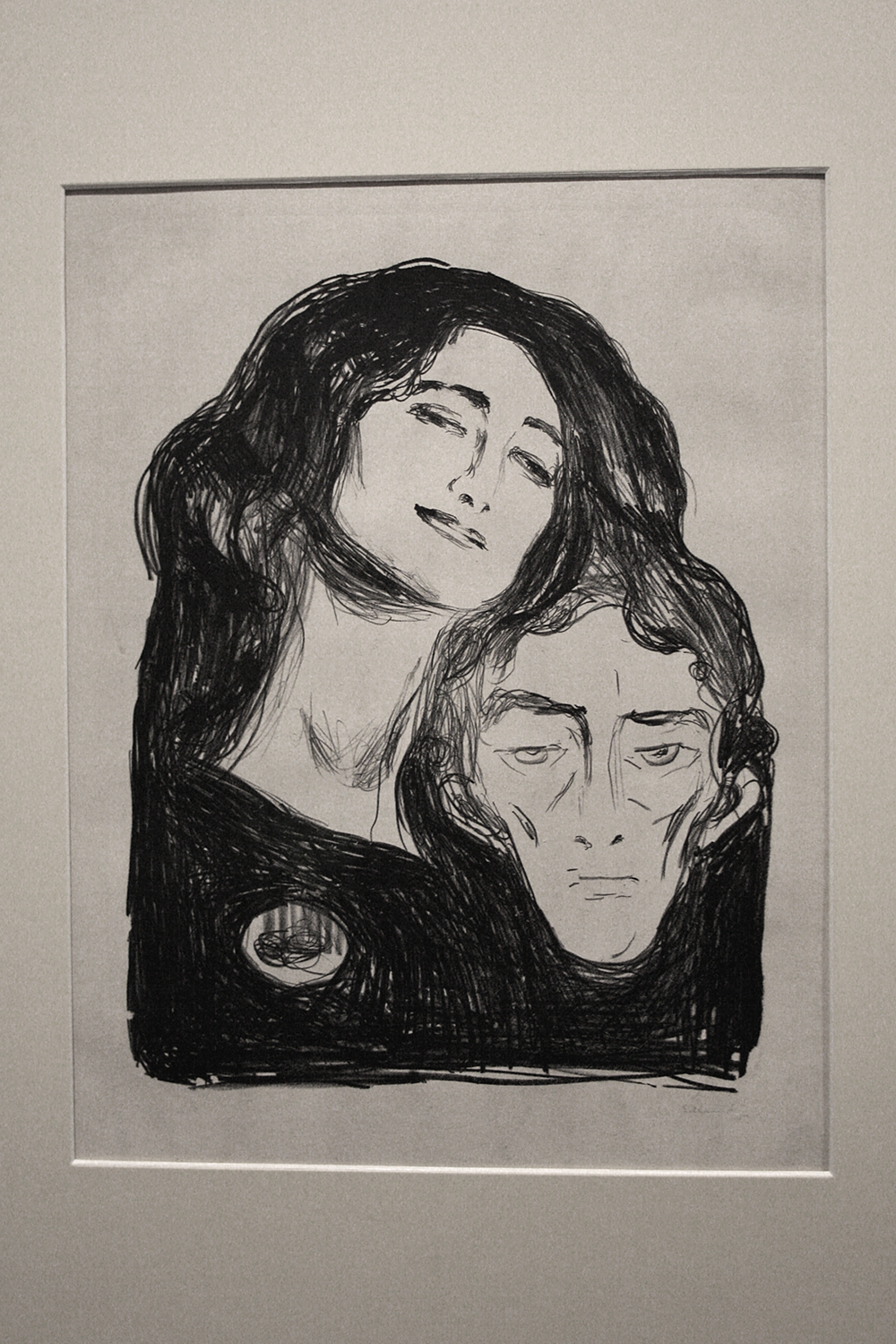

Edvard Munch

Madonna

Dritte Fassung

1895

Als Modell für die fünf „Madonna“-Fassungen, die Edvard Munch zwischen 1894 und 1897 malt, gilt die norwegische Schriftstellerin Dagny Juel.

„Strindberg sah in ihr eine zielbewußte Messalina von letzter Teufelei, vor der man nicht weit genug fliehen konnte und die einen selbst noch in der Ferne am Band hielt. Munch dachte ähnlich und nannte sie, wenn wir unter uns von ihr sprachen, die Dame, was weiter nichts als gebotene Fremdheit besagen sollte […] Vielleicht hat Munch sie gehabt, ich weiß es nicht, nannte sie trotzdem und erst recht die Dame. Vielleicht Strindberg, leicht möglich. Wahrscheinlich hat sie viele gehabt. Besessen hat sie keiner.“ (Julius Meier-Graefe)

„Werner Hofmann suggests that the painting is a ’strange devotional picture glorifying decadent love. The cult of the strong woman who reduces man to subjection gives the figure of woman monumental proportions, but it also makes a demon of her.‘ Sigrun Rafter, an art historian at the Oslo National Gallery, suggests that Munch intended to represent the woman in the life-making act of intercourse, with the sanctity and sensuality of the union captured by Munch. The usual golden halo of Mary has been replaced with a red halo symbolizing the love and pain duality. The viewer’s viewpoint is that of the man who is making love with her.“ [wiki]

Darstellung von Heiligkeit, Darstellung eines Orgasmus, oder beides, you choose.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Rosa Triplex

1867

„Rosa Triplex was inspired by Anthony van Dyck’s painting Charles I in Three Positions … Dante Gabriel Rossetti gave his later works literary and mythical titles, but they have no story. This prioritises their atmosphere and beauty. During this period, Alexa Wilding was Rossetti’s preferred model. He liked her commanding presence.“ [tate.org]

Gustave Moreau

Hélène Glorifiée

1896

In Der Tragödie zweiter Teil (veröffentlicht 1832) läßt Goethe Helena, das Urbild der Schönheit und von Sexualität als Project Mayhem, durch Zeit und Raum zu Faust bringen. Das geflügelte Kind zu Füßen der Helena auf Moreaus Bild ist Euphorion: bei Goethe der Sohn von Faust und Helena. Krieger, Fürst, Poet: niemand hat Besseres zu tun als Helena zu verherrlichen. Damn right.

Jean Delville

L’Idole de la Perversité

1891

Evelyn De Morgan

Medea

1889

Edvard Munch

Salome

1903

Eines meiner liebsten Werke von Edvard Munch ist Die Brosche, eine Lithographie von 1903. Zu sehen ist Eva Mudocci, eine englische Violinistin, die Munch in Paris kennenlernte. Mudocci, die hier 1903 auch als Salome erscheint, war Munchs Geliebte. Munch sagte, sie habe „Augen von tausend Jahren“. Salome jedenfalls sieht glücklich aus.

Odilon Redon

Der mystische Ritter

1869

Ödipus und die Sphinx.

Fernand Khnopff

Who Shall Deliver Me?

1891

Man muß schon deshalb irgendwann im Leben nach München reisen, weil „I lock my door upon myself“ von Fernand Khnopff in der Pinakothek zu sehen ist. Der Titel des Gemäldes ist eine Zeile aus dem Gedicht „Who Shall Deliver Me?“ von Christina G. Rossetti. Christina, die jüngere Schwester des Malers Dante Gabriel Rossetti, schrieb das Gedicht 1866.

Die rätselhafte Schönheit seiner Bilder, der Eindruck des Anderweltlichen, der Eindruck, daß die Seele mit einer Art von beyond in Verbindung steht, all das macht Khnopff für mich besonders faszinierend. Sein bevorzugtes Modell war seine jüngere Schwester Marguerite, und wenn Khnopffs Bildern eine Verheimlichung eingewoben ist, dann gewiß auch ihr Gegenteil, ein Hauch des Inzestuösen liegt über diesen Bildern, es offenbart sich eine mindestens intensive Beziehung, vielleicht eine unglückliche Liebesbeziehung des Malers zu seiner Schwester, mit der er, von der Welt abgeschottet, in einer verwunschenen Villa in Brüssel lebte. Für Khnopff ist Marguerite der Inbegriff der Schönheit, sie ist auch die Frau in „Who Shall Deliver Me?“. Befreiung – vom Eingeschlossensein in sich selbst? Erlösung – vom Verbergenmüssen der geheimsten Sehnsüchte? Errettung – von der Transformation in ein Wesen? Ask these eyes.

Fernand Khnopff

Hérodiade [La Victoire]

c. 1917

Marguerite als Herodias.

Fernand Khnopff

Avec Georges Rodenbach. Une ville morte

1889

Im 1892 veröffentlichten Roman „Bruges-la-Morte“ von Georges Rodenbach erscheint Brügge als Stadt im Dornröschenschlaf, als tote Stadt, als stille Stadt. Auch David Bowie ist mit dieser Stille vertraut: Auf „The Next Day“ von 2013 heißt es in „Dancing Out In Space“: „Silent as George Rodenbach / Mist and silhouette“.

Das Cover, das Guy Peellaert, ebenfalls Belgier, 1974 für Bowies „Diamond Dogs“-LP schuf, könnte auch von Khnopffs Gemälde „Caresses“ von 1896 inspiriert sein, für Till Briegleb „einer der schönsten Momente der Kunstgeschichte, an dem finale Deutung versagen muß“ (sueddeutsche.de, 2019).

Rodenbachs Werk macht Brügge zum Anziehungspunkt für Künstler und Schriftsteller. Der Protagonist des Romans, Hugues Viane, untröstlich über den Tod seiner Frau, zieht nach Brügge, weil es die einzige Stadt für seinen Schmerz ist:

„Und wie traurig war auch Brügge an diesen Spätnachmittagen! So liebte er sie, diese Stadt! Seiner eigenen Traurigkeit wegen hatte er sie ausgewählt, um hier nach der großen Tragödie weiterzuleben. (…) Der toten Frau musste eine tote Stadt entsprechen. (…) In der stummen Atmosphäre unbelebter Kanäle und Straßen hatte Hugues seinen großen Schmerz weniger gespürt, hatte er verhaltener an die Tote gedacht. Er hatte sie besser vor Augen, besser verstanden, fand im Wasser der Kanäle ihr Ophelia-Antlitz wieder (…) Die Stadt, auch sie einst schön und geliebt, verkörperte auf diese Weise seine Klagen. Brügge war seine Tote. Und seine Tote war Brügge.“ (Georges Rodenbach, Das tote Brügge, Stuttgart 2011, 16 ff.)

Khnopff gestaltet für Rodenbachs Roman ein Frontispiz, das die schöne Tote und eine der Brücken Brügges formal in Parallele setzt und so die Identifikation von Stadt und Frau wiedergibt. In einem Essay hat Rodenbach den Gedanken weiter ausgeführt; „Les villes sont un peu comme les femmes“, schreibt er, und Brügge sei wie eine abgesetzte Königin, heute vergessen, früher eine mächtige und prächtige Monarchin. Dies scheint die Erklärung für den wehmütigen Blick auf die Krone.

Gustave Moreau

L’apparition

Undatiert

The head that dripped blood: „This painting picks up the iconography of the famous watercolour of the same title (Musée du Louvre, Department of Graphic Arts, Musée d’Orsay Collection), which inspired J-K Huysmans to write some wonderful passages in his novel A Rebours. It illustrates an episode taken from Chapter XIV of St Matthew’s Gospel. John the Baptist had been imprisoned for having condemned the illegitimate marriage between Herodias and King Herod. Wishing to get rid of this troublesome person, the queen asked her daughter Salome, when she had finished dancing for the king, to ask for the head of John the Baptist as her reward.

This short episode gave rise to many works focusing on the figure of Salome, who did not, however, instigate the crime. But this Jewish princess would excite the imagination of painters to become the archetypal femme fatale. (…) In this painting, we can see: on the left, Herod, hieratic on his throne next to his wife; on the right, the impassive executioner, sword in hand; in the dark background a series of lines describe figures of pagan divinities blending into a strange and disturbing architectural setting, decorated with medieval motifs. This rich ornamental decor, typical of the painter’s style, taken from the most distant centuries and civilisations, make this scene difficult to place in time and space, and adds to its enigmatic character. Gustave Moreau transforms this biblical episode into a fable, a painted poem in which the theme is meant to be edifying as well as a pretext for a dream.“ [musee-moreau.fr]

Gustave Moreau

L’apparition

(Detail)

SALOME

Ah! thou wouldst not suffer me to kiss thy mouth, Iokanaan. Well! I will kiss it now. I will bite it with my teeth as one bites a ripe fruit. Yes, I will kiss thy mouth, Iokanaan. I said it; did I not say it? I said it. Ah! I will kiss it now . . . But wherefore dost thou not look at me, Iokanaan? Thine eyes that were so terrible, so full of rage and scorn, are shut now. Wherefore are they shut? Open thine eyes! Lift up thine eyelids, Iokanaan! Wherefore dost thou not look at me? Art thou afraid of me, Iokanaan, that thou wilt not look at me?

And thy tongue, that was like a red snake darting poison, it moves no more, it speaks no words, Iokanaan, that scarlet viper that spat its venom upon me. It is strange, is it not? How is it that the red viper stirs no longer?. . . Thou wouldst have none of me, Iokanaan. Thou rejectedst me. Thou didst speak evil words against me. Thou didst bear thyself toward me as to a harlot, as to a woman that is a wanton, to me, Salome, daughter of Herodias, Princess of Judaea!

Well, I still live, but thou art dead, and thy head belongs to me. I can do with it what I will. I can throw it to the dogs and to the birds of the air.

That which the dogs leave, the birds of the air shall devour . . .

Ah, Iokanaan, Iokanaan, thou wert the man that I loved alone among men! All other men were hateful to me. But thou wert beautiful! Thy body was a column of ivory set upon feet of silver. It was a garden full of doves and lilies of silver. It was a tower of silver decked with shields of ivory. There was nothing in the world so white as thy body. There was nothing in the world so black as thy hair. In the whole world there was nothing so red as thy mouth. Thy voice was a censer that scattered strange perfumes, and when I looked on thee I heard a strange music. Ah! wherefore didst thou not look at me, Iokanaan?

With the cloak of thine hands, and with the cloak of thy blasphemies thou didst hide thy face. Thou didst put upon thine eyes the covering of him who would see his God. Well, thou hast seen thy God, Iokanaan, but me, me, thou didst never see. If thou hadst seen me thou hadst loved me. I saw thee, and I loved thee. Oh, how I loved thee! I love thee yet, Iokanaan. I love only thee . . .

I am athirst for thy beauty; I am hungry for thy body; and neither wine nor apples can appease my desire. What shall I do now, Iokanaan? Neither the floods nor the great waters can quench my passion. I was a princess, and thou didst scorn me. I was a virgin, and thou didst take my virginity from me. I was chaste, and thou didst fill my veins with fire . . .

Ah! ah! wherefore didst thou not look at me? If thou hadst looked at me thou hadst loved me. Well I know that thou wouldst have loved me, and the mystery of Love is greater than the mystery of Death.

HEROD

She is monstrous, thy daughter; I tell thee she is monstrous. In truth, what she has done is a great crime. I am sure that it is a crime against some unknown God.

HERODIAS

I am well pleased with my daughter. She has done well.

[Oscar Wilde]

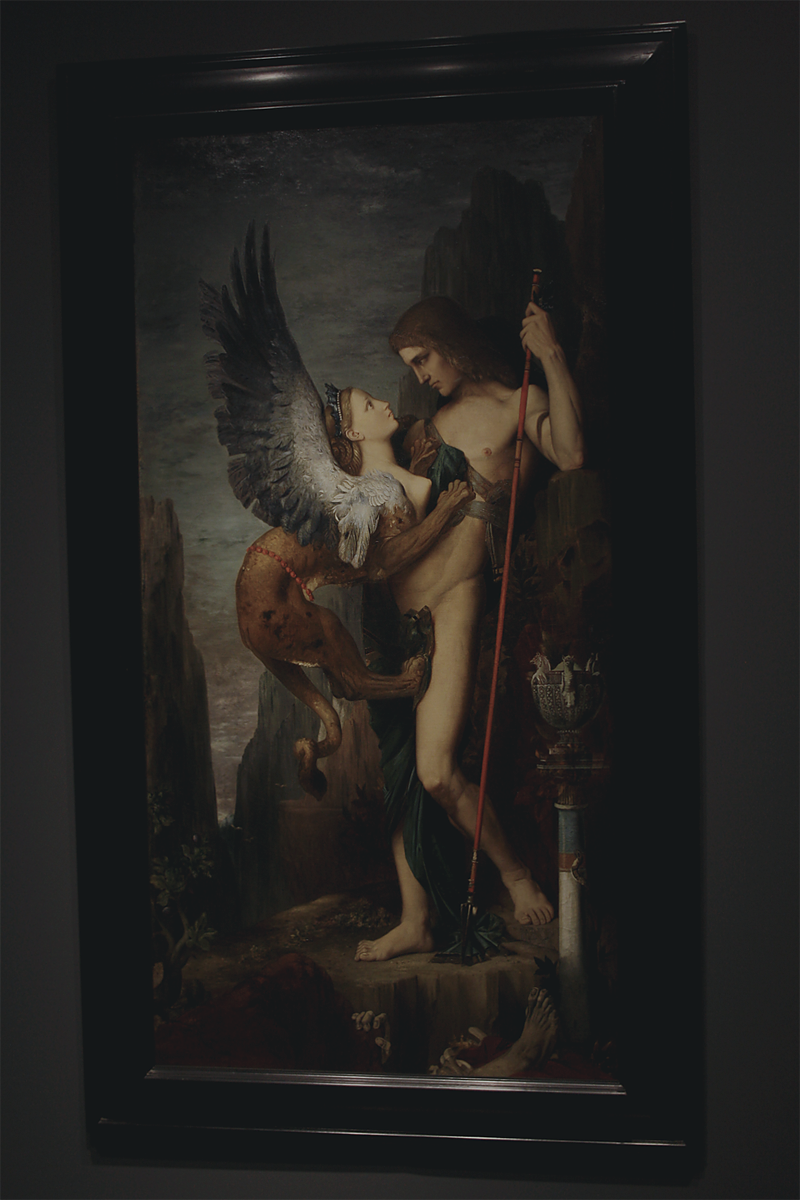

Gustave Moreau

Œdipe et le Sphinx

1864

Das ist ein so leidenschaftlich intimer Moment zwischen der Sphinx und Ödipus, ihr Aneinander und ihr Blickkontakt so intensiv, daß man als Beobachter den Blick abwenden müsste, wenn man den Blick abwenden könnte.

Franz von Stuck

Haupt der Medusa

um 1892

Alle Fotos CE

One reply on “Femme Fatale – Kunsthalle Hamburg”

Danke für die wunderbaren bild- und wortreichen Einblicke in so manch‘ Femme fatale.

Ja, das Leben ist schön … (lieber Blixa) ;-)

LikeGefällt 1 Person