Looking back, more than twenty years later, Janowitz considered that his distinctive contributions to the conception were fourfold. First, the atmosphere of mystery inspired by memories of his home-town Prague. Second, the sense of foreboding he had already demonstrated in his play PRAGER FASTNACHTSSPIEL UM 1913 (1913). Third, the inspiration of a bizarre incident which he witnessed in Hamburg in 1913; at an amusement park on the Reeperbahn, beside the Holstenwall, he had noticed a young girl, ‚drunken with the happiness of life‘. Fascinated, he followed her, but she disappeared into some bushes, from which emerged, moments later, an unremarkable bourgeois man. Next day he learned that the girl had been murdered. Finally, and most important in Janowitz’s view, was the pathological mistrust of ‚the authoritative power of an inhuman state gone mad‘ which he had acquired through five and a half years of military service. [1]

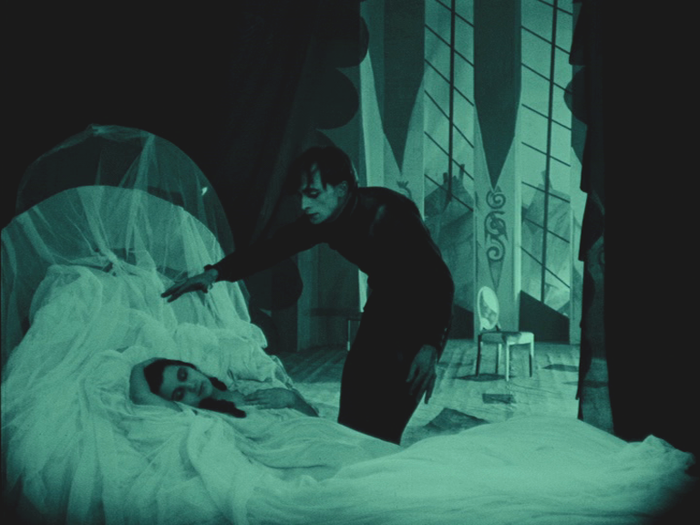

Dominating all is the performance of the androgynous and sexually fascinating Veidt – concentrating Herculean struggle into the raising of the lids that cover the unearthly glare of his eyes; gliding along the wall of Jane’s house like a shadow that has lost its body; transformed from seraph to vulpine beast when Jane resists. [2]

In the outcome, the audience were spellbound. A woman screamed out at the moment when Cesare’s eyes open. Several (at least according to Janowitz) fainted, groaned or shrieked when Cesare abducted the sleeping Jane. [3]

The scene of Cesare’s awakening remains one of cinema’s most unforgettable sequences. […] When the box is opened, Cesare’s eyes are tightly shut. His physical effort is now concentrated not on the fight for breath but on the struggle to open his eyes, culminating in the ever-haunting moment when the huge, staring, anguished orbs are revealed in their full phenomenal extent. Nor does Cesare now weaken and fall. Gently guided by Caligari’s short pointer-stick, he extends his lower arms, and takes a few effortful, robotic steps forward. [4]

Doch er kommt nicht weit, der traurige Todes-Clown. [5]

Pierre Philippe schreibt: „Das Wunder dieses Films liegt darin, daß er für immer die Kühnheiten bewahrt, die ihn geschaffen haben, und daß er nie aufhört, uns seine schwarze Tinte in unsere ewig jungfräulichen Augen zu schleudern … Das Wunder dieses Films ist es, daß er seine eigenen Detektive überwindet, um allen nur ausdenkbaren Phantasien Platz zu machen.“ [6]

„Wir drei Maler schafften immer bis in die Nacht hinein, wie in einem Taumel.“ (Hermann Warm)

Anfang 1920 tauchen überall in Berlin expressionistisch gestaltete Plakate auf mit der geheimnisvollen Botschaft: „Du musst Caligari werden!“

„Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari“ feiert am 26. Februar 1920 im Marmorhaus am Kurfürstendamm Premiere.

In Pariser Kinos läuft der Film für die nächsten sieben Jahre.

[1] David Robinson, Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari, London 1997 (BFI Film Classics), 10

[2] Robinson, 29

[3] Robinson, 47

[4] Robinson, 64 ff.

[5] Hans Schifferle, Die 100 besten Horror-Filme, München 1994, 32

[6] Schifferle, 32